Author: Carlos Andrés García Carvajal (Bogotá, Colombia)

“We propose new symbols in public spaces. Symbols that apologize for violence are imposed in all public spaces in Colombia, we have to look for other symbols that reconcile us with all the actors that exist in Colombia” (Secretary of the Indigenous Authorities Movement of Colombia, 2021).

The recent "national strikes" in Colombia have made visible the need to ask about the relation between the uses of the public space and their relationship with troubled pasts and present injustices and the need to understand reconciliation as a broad process that affects and even includes people who have never been involved in an armed conflict. For this reason, this essay will begin by presenting the connection between reconciliation and peacebuilding in divided societies, and then present a quick context of the current situation in Colombia, in order to address the question of what is the sense of working on reconciliation in a divided society? The resources used are data from the government of Colombia, which will allow presenting a current social and political panorama; the interviews carried out with three Colombian social leaders, which will allow having a comprehensive perspective of the challenges and possibilities of reconciliation today; and the experience accumulated in my work at the University of Los Andes. This, framed within the general themes addressed throughout the course. In addition, some photographs were used to better understand the artistic actions that are currently being carried out in the country to reconfigure, reappropriate, or resignifying public spaces. This work is carried out within the framework of the “Peace Building in Divided Societies” summer course, offered by the Peace Academy Foundation (PAF) developed between July and September 2021.

Thinking in peace building in divided societies is thinking in the importance of reconciliation. Which is why when I saw this summer course, I related it with my experience in the investigation “Transform Social Injustices and Create New Social Agreements: Pedagogies and politics of reconciliation”, from Professor Fernando Serrano Amaya (Los Andes University, Colombia). I have had the opportunity to participate in this project since 2019, where we have investigated the pedagogies and politics of reconciliation in Australia, Colombia and South Africa from the practices that are done in the name of this concept. In Professor Serrano Amaya’s investigation, reconciliation is understood as a “time device” because it makes possible to “deal with a troubled past and handle with present injustices to change the future” (Serrano Amaya, 2021). This is intended to be a comprehensive definition, following Renner's (2021) assertions that semantic flexibility of reconciliation is not a problem but a potential. I link the above with Pr. Stanton’s (2021) phronetic knowledge uses because Serrano Amaya argues that for understanding reconciliation, we need to understand the practices that people do in its name. In other words, it is necessary to comprehend the complex set of social practices lead by social actors on the promotion of social change (Renner, 2021), the “practical wisdom” (Stanton & Kelly, 2015), to understand in a comprehensive way the reconciliation.

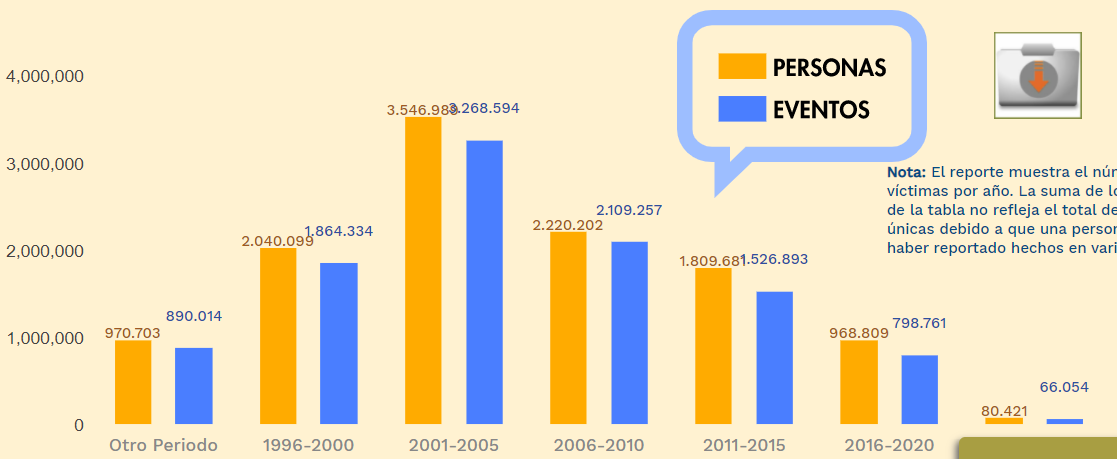

The issue of reconciliation is raising in the context of the post-agreement between the FARC-EP guerrilla and the Government. Although the armed conflict (or conflicts) indeed persists in Colombia, due to the presence of multiple illegal armed actors, standing out the ELN (National Liberation Army) left-wing guerrilla and the AGC (Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia) right-wing neo-paramilitary group; It is also true that it can be said that the intensity of the armed conflict has decreased compared to the years before the signing of the “Final Agreement”[1]. The main example of this is that in the first five years after the Agreement was signed (2016 – 2020), the number of victims has decreased by 53.5% compared to the number of victims during the five years prior to its signing (2011 -2015) (see graphic 1). This has even been the most peaceful five-year period in the last 25 years.

Graphic 1. Victims of the armed conflict in Colombia per quinquennium. In orange, numbers for victimized people. In blue, numbers for violent evets. Colombian Government, July 2021.

Graphic 1. Victims of the armed conflict in Colombia per quinquennium. In orange, numbers for victimized people. In blue, numbers for violent evets. Colombian Government, July 2021.

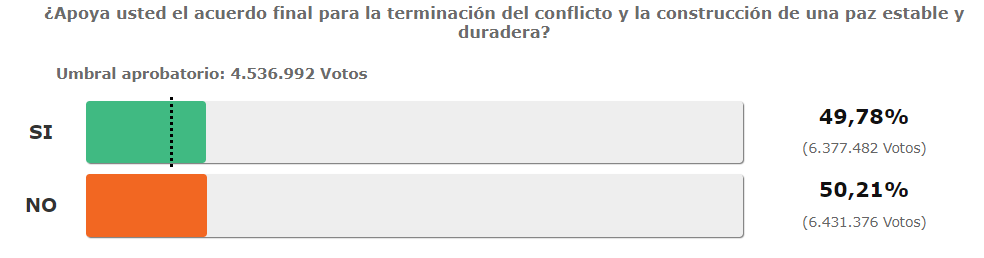

Nevertheless, internal politics has dragged Colombian society to a point of maximum “polarization”, where debate and the exchange of ideas have been relegated to the disqualification between “paramilitary” or “fascists” (when someone support the government politics or has more conservative ideas) and “Marxist partisan” or “castrochavista” (when someone criticizes the government or has more progressive ideas). This state of “polarization” has led many people to have a radicalized position against the Final Agreement, which was reflected in the victory of "no to the Agreement" in the 2016 plebiscite (with a difference of less than 0.5%) and the victory in the legislative and presidential elections of the political party that most opposed to the peace process. In these last ones, the second round was between the leftmost and rightmost political party options. Since then, the divisions between citizens with opposing thoughts have become more marked.

Colombian 2016 plebiscite. “Do you support the final agreement for ending the conflict and building a stable and lasting peace? Yes: 49,78%. No: 50,21%”. Colombian National Registry, 2016.

Colombian 2016 plebiscite. “Do you support the final agreement for ending the conflict and building a stable and lasting peace? Yes: 49,78%. No: 50,21%”. Colombian National Registry, 2016.

The recent "National Strikes", called by the media the “social outbreak”, lived in the last three years are framed in this political context. Although many of the organizers consider that it is a great National Strike that has been intermittent, three important moments can be identified. The first one starts on November 21, 2019. It lasted more than a month and involved the imposition of curfews in Bogotá for the first time since the current political constitution was signed (1991). The second one, September 9, 2020, was shorter, but more intense, and was characterized by occurring during full strict quarantine and by the transformation that many police stations had, which were converted into cultural or community centers. The most recent began on April 28, 2021, was the longest strike in the country's history, lasting about two months.

A police station transformed into a “cultural center” by the strikers in Bogotá, September 12, 2020. Photography: Germán Enciso, 2020.

The causes and objectives of each strike have been as diverse as the social groups who have participated in them. However, two of the main points have been the protest against police violence and abuse, which has been constantly on the rise, and the demand for the implementation of the Final Agreement. In the same way, various forms of protest have spread and popularized, much of them framed within art and culture and developed in various public spaces. From acts without major confrontations, such as the realization of murals, songs and concerts; to others where confrontation with the police, local authorities and other citizen groups was necessarily resorted to, such as the aforementioned artistic shots of police stations and the resignification of statues and public monuments.

What these practices have made visible is an interest and an urgency to democratize the spaces that, on paper, are public, through participatory, popular, community and debureaucratized instances. A large part of these events have been confrontations with violent and colonial logics that have been assumed as normal and desirable: particularly, the fact that "the public" has been defined and continues to be maintained by the colonial, class and elitist powers. In the words of Boaventura de Sousa (2010), these acts have been efforts to promote popular participation and the recognition of these "very different" knowledge, traditions and repertoires that have been "produced as non-existent."

It is for this reason that various sectors have appealed to reconciling speeches, such as the "social dialogues" promoted by the national administration. Beyond the political instrumentalization that is given to Reconciliation, it becomes important in the context of the social wounds that have been made visible in public spaces during these national strikes: from very conjunctural aspects, such as the possibility of creating a mural of protest to the government on a wall authorized by a mayor's office, which generates tensions among the citizens; even the claims for statues that have accompanied a square or a viewpoint for more than a century, but that exalt figures and symbols of colonialism and repression that the ethnic peoples of the country lived and still live.

With the intention of understand better the possibilities and challenges of reconciliation in this national context of social division, three social leaders representing three different sectors (the Misak indigenous people, popular youth activism, and artistic collectives) have been interviewed, who claim their agendas through three different practices (interventions on public monuments, muralism and popular radio stations) from three different regions of the country (Norte de Santander, Valle del Cauca and Cauca).They are: Diana Mery Jembuel Morales, from Causa, part of the Misak indigenous people, Awarded as the best Afro-indigenous journalist in Colombia in 2020 by the Colombian Public Media System (RTVC); Isaac García, from Norte de Santander, social and political young leader, President of the Community Action Board in Cúcuta city, Youth Representative before the Municipal Victims Table and peace counselor before the Government of Norte de Santander; and María Juliana Soto, from Cali, Valle del Cauca, member of the alternative popular radio collective Noís and university professor.

In this way, they were asked about the historical debts that exist around the representation of plurality in public spaces in the country. In this regard, Diana Mery considers that the debt for indigenous peoples in Colombia lies in non-compliance with the Political Constitution. Even though this is a diverse and multicultural Constitution, it is not applied in its entirety, as well as its application is even poorer outside of large urban centers. For this reason, despite the fact that indigenous peoples are legally protected, in practice they are excluded from important decisions in public life, forcing them to carry out demonstrations and to take action as the only way to be heard.

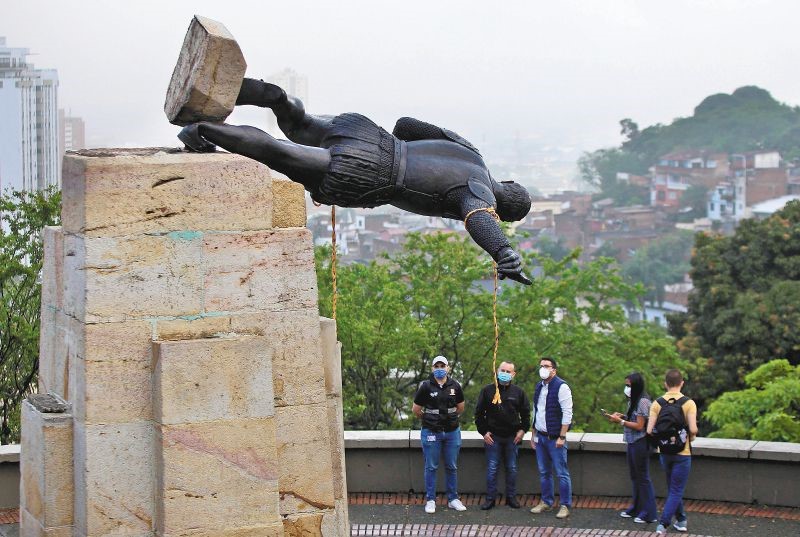

The Statue of the Spanish conqueror Sebastián de Belalcázar come down on April 28, 2021, in the city of Cali by members of the Misak people. Photography: AFP, 2021.

The Statue of the Spanish conqueror Sebastián de Belalcázar come down on April 28, 2021, in the city of Cali by members of the Misak people. Photography: AFP, 2021.

For Isaac, the lack of representation that alternative sectors have in the country's public spaces reflects an “organic crisis” based on the lack of credibility and legitimacy that the Colombian State institutions have. It is precisely the homogenizing processes that these institutions have advanced, in the search to make the divergent actors and historical social claims invisible, which have resulted in increasingly violent responses from society. As there are no authorized spaces to demand a dignified life, young people have turned to the streets. In other words, making a graffiti or a mural against the government has an intention beyond art (or vandalism): today it is a way to dispute “the common” with those who have always had the power to say and do what they want.

Mural "Psychopath Government" made by Isaac's youth group in the city of Cúcuta. After this work, some people were threatened with death by regional leaders of the government political party. Photography: Bella Bobrek, 2021.

Mural "Psychopath Government" made by Isaac's youth group in the city of Cúcuta. After this work, some people were threatened with death by regional leaders of the government political party. Photography: Bella Bobrek, 2021.

In the case of María Juliana, the historical debt that Colombia has around representation has to do with listening: listening to the diversity of understandings and perspectives. While listening appears to be a passive thing, it must be an active cause. When we listen with attention and empathy and not only with the desire to speak, a transformative and transcendental dialogue becomes possible. In this way, it is active listening that can make it possible to reach an agreement on what is common and, with it, make all of us feel more represented in public spaces.

Radio performance "The night of 21N [2019] in Cali: From fear to reconciliation". Photography: Noís Radio, 2020.

Radio performance "The night of 21N [2019] in Cali: From fear to reconciliation". Photography: Noís Radio, 2020.

After this, we ask about How does a monument in a city, which has been there for decades, suddenly becomes a point of contention? Diana says that indigenous people historically have never had the right to express themselves and the privilege to speak. The objective of the society was to eliminate their ancestral knowledge and their indigenous thoughts. But now the Misak people have new generations, who have been able to formally study and finishing university studies. It was these new generations who gave them the strength to start coming down statues, with the aim of sending a message to Colombia and “the entire continent”. “Our objective is not to destroy a statue, but with it to begin to destroy the colonial thought and the patriarchal forms that have been imposed on us”. Thanks to this process, the youngest, the Misak children, today can think critically: they see a statue and they wonder, Is this statue worth it? Or is the man in the statue one of the many murderers of our leaders? Coming down a monument is also an invitation to all people to ask themselves these questions. “Because it is very good to consider everything we have learned from Europe, but it is time for you to learn what the indigenous, the black, and the peasants have to say”.

Artistic intervention to a monument come down in Bogotá: an important avenue named in honor of a Spanish conqueror is now known informally as "Misak Avenue". Photography: Eskaparate.com, 2021.

Artistic intervention to a monument come down in Bogotá: an important avenue named in honor of a Spanish conqueror is now known informally as "Misak Avenue". Photography: Eskaparate.com, 2021.

Finally, after asking about the sense of talking about reconciliation in a context as complex as the one currently going through Colombia and taking up what was previously written, different conclusions are reached. The most evident is that reconciliation is not an easy process, since talking about the crisis is complicated, as Isaac recalled. For this reason, thinking about a national reconciliation is a difficult and long-term bet, which has already made progress, such as the Final Agreement with the FARC; but also, setbacks, such as the incorrect or even instrumentalized implementation of it.

The conversation with Juliana makes it possible to recall that, despite the difficulty that exists in achieving national reconciliation, reconciliation is already happening in other (littler) places. Regardless of the difficulties, reconciling as a community is the only way we have to reach new social realities. This is a particular struggle that we have in Colombia since we have to work to achieve reconciliation in a country that is still at war. Just as a peace agreement has to be implemented in a country where there are still other armed conflicts. For this to make sense, we have to stop thinking about "reconciliation" and start thinking about "reconciliations." Likewise, working to configure new, more cohesive societies will depend on the capacity that we have as individuals to actively listen to the other and have the will to understand what others have to say to us: to care about our neighbors, create community, recognize others, and accept other´s contexts. Community reconciliation must be worked on regardless of whether or not the national government cares about peace and reconciliation.

Also, for these reconciliation processes to be possible, those who have so far been excluded must be included. The transition to less divided societies will take place when the popular sectors, such as the indigenous, are finally considered. And these are needs that cannot be left only in speech. The historical memory of indigenous peoples must be recognized and vindicated, but it is even more important that it be recognized that there are historical material effects that continue to exclude them from the rest of society. "They stripped us of our lands and confined us in the mountains of Colombia or barren valleys", says Diana. "Reconciliation with us is not only to dismantle the colonial figures and discourses that started this genocidal process but to seek how we can exist living well, with dignity".

In conclusion, the challenges around reconciliation in a society as divided as that of Colombia are very varied and depend on the perspective from which it is viewed. For this reason and taking up the need to have a comprehensive definition of reconciliation, there cannot be a single answer on the sense or meaning of reconciliation in a divided society. However, this is not a problem to address the issue, nor to not actively work in the processes that lead to the social changes that are needed to be able to reach a panorama of reconciliation. For this, it is important to concentrate on understanding the different practices that are done in its name, which, despite sometimes appearing different and contradictory, are certainly the only way to fully understand the limits and possibilities of reconciliation. Just as in Bosnia and Herzegovina practices framed in the komsiluk (good neighborliness) were recorded, such as the coffee visits of women (Helms, 2010), in Colombia the work must continue to understand the idiosyncratic forms that have been advanced to achieve la convivencia (to life together) and reconciliation. In this particular case, some artistic efforts were presented around representation in public space, but without a doubt, the way to better understand this scenario is more complex and more complicated.

References

Colombian Government (July 2021). Official registry of victims [Spanish]. Retrieved from: https://www.unidadvictimas.gov.co/es/registro-unico-de-victimas-ruv/37394

Colombian National Registry, 2016. Plebiscite Precount [Spanish]. Retrieved from: https://elecciones.registraduria.gov.co/pre_plebis_2016/99PL/DPLZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZ_L1.htm

de Sousa Santos, B. (2010). Descolonizar el saber, reinventar el poder. Montevideo: Ediciones Trilce – Universidad de la República.

El Tiempo [El Tiempo] (April 28, 2021). Indígenas Misak explican por qué tumbaron la estatua de Sebastián de Belalcázar en Cali [Video] [Spanish]. Youtube. Retrieved from:

Helms, E. (2010). The gender of coffee: Women and reconciliation initiatives in post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina. Journal of Global and Historical Anthropology.

Renner, J. (2021). The Local Roots of the Global Politics of Reconciliation: The Articulation of 'Reconciliation' as an Empty Universal in the South African Transition to Democracy. London: Millennium - Journal of International Studies.

Stanton, E. & Kelly, G. (2015). Exploring Barriers to Constructing Locally Based Peacebuilding Theory: The Case of Northern Ireland. The Hague: International Journal of Conflict Engagement and Resolution.

Serrano Amaya, J.F. (2021). “Reconciliation as social pedagogy: restrictive and alternative models to deal with past and present injustices”. In: Louis, T; Peters, S; Molope, M. (ed.) (2021): Dealing with the Past. Transregional Perspectives and Experiences from Africa, Latin America and Europa [preprint archive]. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Stanton, E. (2021). Using Phronesis to Progress Peace. [Proof]

Endnotes

[1] Final agreement to end the armed conflict and build a stable and lasting peace.